Traditional IRAs versus Roth IRAs: Which is Better for Dividends?

For investors looking to build a dividend-paying nest egg for their golden years, an individual retirement account (IRA) is the most common arrangement.

Any number of investment options may be placed within an IRA, and in exchange for showing some initiative and taking on part of the responsibility of financing your own retirement, Uncle Sam agrees to defer taxation on money within IRAs.

Two types of IRAs exist — the Traditional IRA and the Roth IRA. While both share a significant number of features, there are also major differences between the two.

It’s these similarities and shared characteristics that often confuse many consumers.

For investors holding dividend stocks in IRAs, this matter can appear even more complicated due to the nature of the dividend itself, given that such securities generate additional income within those retirement accounts.

Let’s take a closer look at IRAs, how they are taxed, and the effects of holding dividend-paying stocks within them.

Traditional IRA Basics

The Traditional IRA was the result of the American public’s demand for a tax-favored retirement arrangement. In 1974, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, ERISA, was passed and part of that legislation was the creation of the Traditional IRA.

For the 2018 tax year, IRA account owners may deposit a combined total of $5,500 or 100% of earned income, whichever is the lesser amount. If you’re older than 50, Uncle Sam will allow you to put in an additional $1,000 as a “catch-up” contribution.

Any money deposited into a Traditional IRA generates a dollar-for-dollar income tax deduction. Plus, growth on the investments within the IRA will not be taxed — provided, of course, that the money remains within the account. So, the tradeoff for setting aside a portion of your current income to be used when you retire is tax-deferred accumulation.

According to IRS regulations, money within an IRA must remain untouched until the account owner reaches the age of 59-1/2. Withdrawals from an IRA will create an income tax liability, as the amount withdrawn is considered current earnings and will be taxed at the owner’s then-marginal tax rate.

So, it is important to realize that IRA withdrawals can actually have a rather significant impact, particularly if your income is on the cusp of breaking through to the next tax bracket.

If money is withdrawn from an IRA prior to the year in which you reach age 59-1/2, a 10% penalty will be due in addition to the current income taxes. Obviously, this is more relevant and will have a more dramatically negative impact on larger accounts and higher early withdrawal amounts.

Another potentially important facet of the Traditional IRA is its upper age limit. Since the money within the IRA has yet to be taxed, the IRS will force you to begin taking distributions once you reach age 70-1/2.

This is because the IRS isn’t willing to wait forever for the taxes due on the money within your account. So, a somewhat complex calculation is performed annually beginning with the year in which you reach age 70-1/2, and the result of that computation is your Required Minimum Distribution, or RMD.

The RMD is an exact dollar amount that you must withdraw from your IRA during that year. The figure is based on your age and the total value of your account. Your age is taken into consideration because the average lifespan is viewed as the target date by which your account should be completely emptied and all tax liabilities satisfied.

Additionally, once you reach age 70-1/2 you can no longer continue to deduct contributions into your Traditional IRA on your income tax forms.

Roth IRA Basics

The Roth IRA is a variation of the Traditional IRA; these accounts share some important IRS criteria and restrictions, yet contain major differences that can have a potentially significant impact on your financial future. It wasn’t until the passage of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 that Americans had access to anything other than the Traditional IRA.

Roth IRAs present an alternative to the tax-deductible contributions and tax-deferred growth of Traditional IRAs. The basic premise of the Roth IRA is the same, as are the contribution maximums and age 59-1/2 withdrawal restrictions. Any interest earned or generated by the investments within a Roth IRA will not result in current tax liability.

The two major differences with a Roth IRA are: (1) no current-year income tax deduction is given for contributions, and (2) qualified withdrawals (those made after age 59-1/2) are received completely tax-free.

So, in exchange for earmarking some of this year’s income for use during retirement, while still paying income taxes on those contributions, Uncle Sam has agreed to give you a pass on the growth and interest that might accumulate in a Roth IRA. There is no maximum amount of tax-free growth and Roth IRAs do not have RMDs, either.

One thing to keep in mind is that a distribution from a Roth IRA taken prior to age 59-1/2 will not result in any additional taxes or penalties on the portion of the withdrawal that’s considered a return of earlier contributions. However, full income taxes will be due and the 10% early withdrawal penalty will be assessed on the withdrawn growth.

Additionally, to withdraw money without paying penalties and taxes, initial contributions to a Roth IRA must have taken place at least five years prior to the withdrawal.

IRA withdrawals use the first-in-last-out, or FILO, structure, which means partial distributions are considered to come from the account’s growth first. Only after the growth has been withdrawn will distributions be considered a return of contributions.

Think of it this way. You’re going to pay the income tax on your IRA contributions, whether it’s years down the road when you withdraw it from your Traditional IRA or now when you deposit it into your Roth IRA. The question, then, is whether you’d rather have a deduction on this year’s taxes or unlimited tax-free growth potential.

Typically, the Roth IRA is extremely attractive for investors who are younger and plan on working for at least the next two or three decades. Paying the income taxes on Roth IRA contributions now, while salaries and tax brackets are most likely less than what they’ll be 20 or even 30 years down the road, makes a lot more sense compared to taking a relatively insignificant deduction now and paying, potentially, much higher taxes during retirement.

Roth IRAs versus Traditional IRAs: Which is Better for Dividend Stocks?

It goes without saying that using IRAs to achieve tax-deferred or tax-free growth is a benefit that all investors should take advantage of. The next question is whether a Roth IRA or Traditional IRA makes more sense for the long haul. As with many things in investing, the answer is, “It depends”.

A Traditional IRA might not be the best idea for dividend stocks if you expect your tax rate at retirement to be higher than it is today. Sure, you’ll avoid paying taxes on those dividends for years, potentially decades, while they remain shielded in your IRA, but when you finally begin making withdrawals you’ll be paying ordinary income tax rates.

This means that if tax brackets are exactly the same when you retire as they are right now, your tax bracket could potentially be as high as 37%. Of course, that’s today’s highest income tax bracket, but there’s no way of predicting what those brackets will look like in 10, 15, or 20+ years. RMDs can further complicate tax planning when they kick in, and who knows what the treatment (and availability) of Social Security benefits will be like in the distant future.

Based on today’s rates, if your income is above $38,700 you’d be in the 22% tax bracket. Considering that the qualified dividends and long-term capital gains tax rate is 15% for that level of income, you’d be paying more taxes on dividends withdrawn from a Traditional IRA than if you’d held those stocks in an ordinary non-IRA brokerage account.

The tables below show the tax rate differences between qualified dividends held in taxable, non-IRA brokerage accounts, which are taxed at the long-term capital gains rate between 0% and 20%, and ordinary income, which is how Traditional IRA withdrawals are taxed when the time comes.

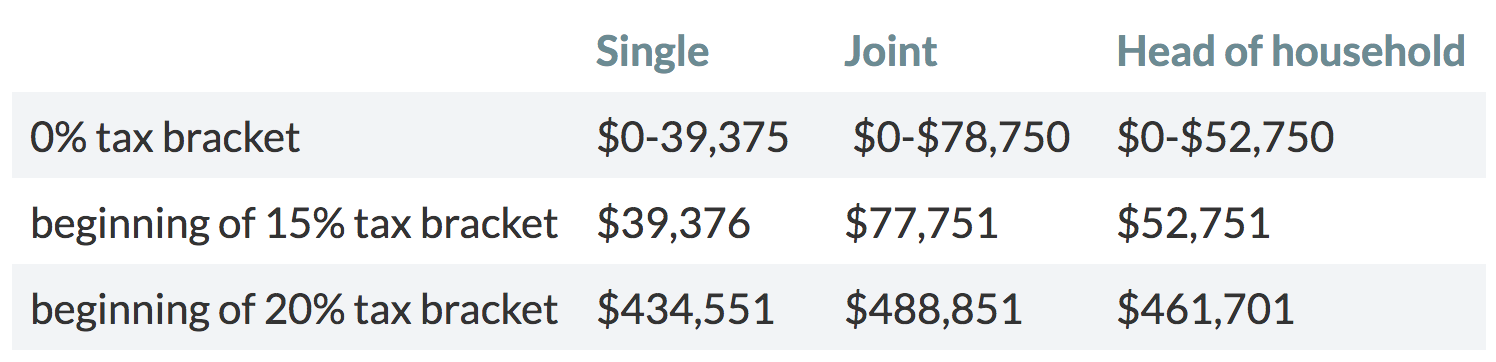

Following the passage of tax reform in late 2017, here are the cutoffs for taxes on long-term capital gains. These are the rates you pay for qualified dividends held in taxable accounts based on your income level:

As you can see, these rates compare very favorably to ordinary income rates which are assessed to Traditional IRA withdrawals:

Holding dividend stocks in a Roth IRA rather than a Traditional IRA can be more advantageous down the road. Within a Roth IRA, those dividends can accumulate tax-free for as long as you want and you’ll never have to pay taxes on them. This is a solid option for many investors who plan to live off dividends and expect their tax rate at retirement to be higher than it is today.

However, maintaining a blend of Traditional IRA, Roth IRA, and taxable accounts can help maximize after-tax income in retirement. No one knows what tax rates will be over the coming decades, so having the option to simultaneously withdraw income from various accounts with different tax treatments can provide nice flexibility.

However, maintaining a blend of Traditional IRA, Roth IRA, and taxable accounts can help maximize after-tax income in retirement. No one knows what tax rates will be over the coming decades, so having the option to simultaneously withdraw income from various accounts with different tax treatments can provide nice flexibility.

That being said, choosing stable, dependable dividend stocks with a solid history of steady dividend growth is essential to maximizing the long-term profit potential of any account.