A Short Lesson on REIT Taxation

Since their inception in 1960, real estate investment trusts (REITs) have become a popular option for income investors.

Investing in REITs can offer high dividends and capital appreciation potential, all while making it easy to gain exposure to property markets without the headaches that come with holding real estate directly.

However, REIT taxes are an important issue to understand. Before explaining how REITs are taxed, let’s quickly review how REITs work.

Investing in REITs can offer high dividends and capital appreciation potential, all while making it easy to gain exposure to property markets without the headaches that come with holding real estate directly.

However, REIT taxes are an important issue to understand. Before explaining how REITs are taxed, let’s quickly review how REITs work.

What Is a Real Estate Investment Trust?

A REIT is an independent investment company that purchases real estate for the sole purpose of generating regular, predictable income. This income is derived from lease agreements with tenants who pay rent to use a REIT's property.

Through extensive portfolios, which typically consist of commercial properties such as corporate offices, warehouses, shopping centers, and apartment complexes, REITs provide income to shareholders in the form of dividends.

Legally, a REIT must annually distribute at least 90% of its taxable income in the form of dividends to its stockholders. This allows REITs to pass on their tax burden to shareholders rather than pay federal taxes themselves.

Taxation of REITs

Although REIT investors receive a standard 1099 form at tax time, the income tax liability faced by REIT shareholders can still be complicated.

Dividend payouts received by REIT investors in taxable accounts can consist of three components, each with its own tax consequences:

Dividend payouts received by REIT investors in taxable accounts can consist of three components, each with its own tax consequences:

- Ordinary dividends make up the bulk of dividends paid by most REITs. They come from a REIT's taxable income and are taxed as ordinary income at an investor's marginal tax rate.

- Capital gains distributions occur when a REIT sells real estate assets and realizes a profit. Unlike ordinary dividends, these distributions are treated like any other capital gain and subject to preferential rates.

- Return of capital (ROC) results from distributions that exceed a REIT's profits. ROC distributions are not taxed when received but instead reduce an investor's cost basis, deferring taxes until shares are sold. ROC usually isn't a red flag because a REIT's a taxable income is reduced by non-cash deprecation charges (despite real estate typically rising in value).

This information is a lot to take in, and the notion of performing all those calculations when tax time comes around is enough to give anyone a headache.

Fortunately, REITs do much of the heavy lifting for you; at the end of each calendar year, shareholders will receive forms 1099-DIV and 8937.

These forms breakdown the amount of ordinary dividends, capital gains distributions, and ROC paid for the year.

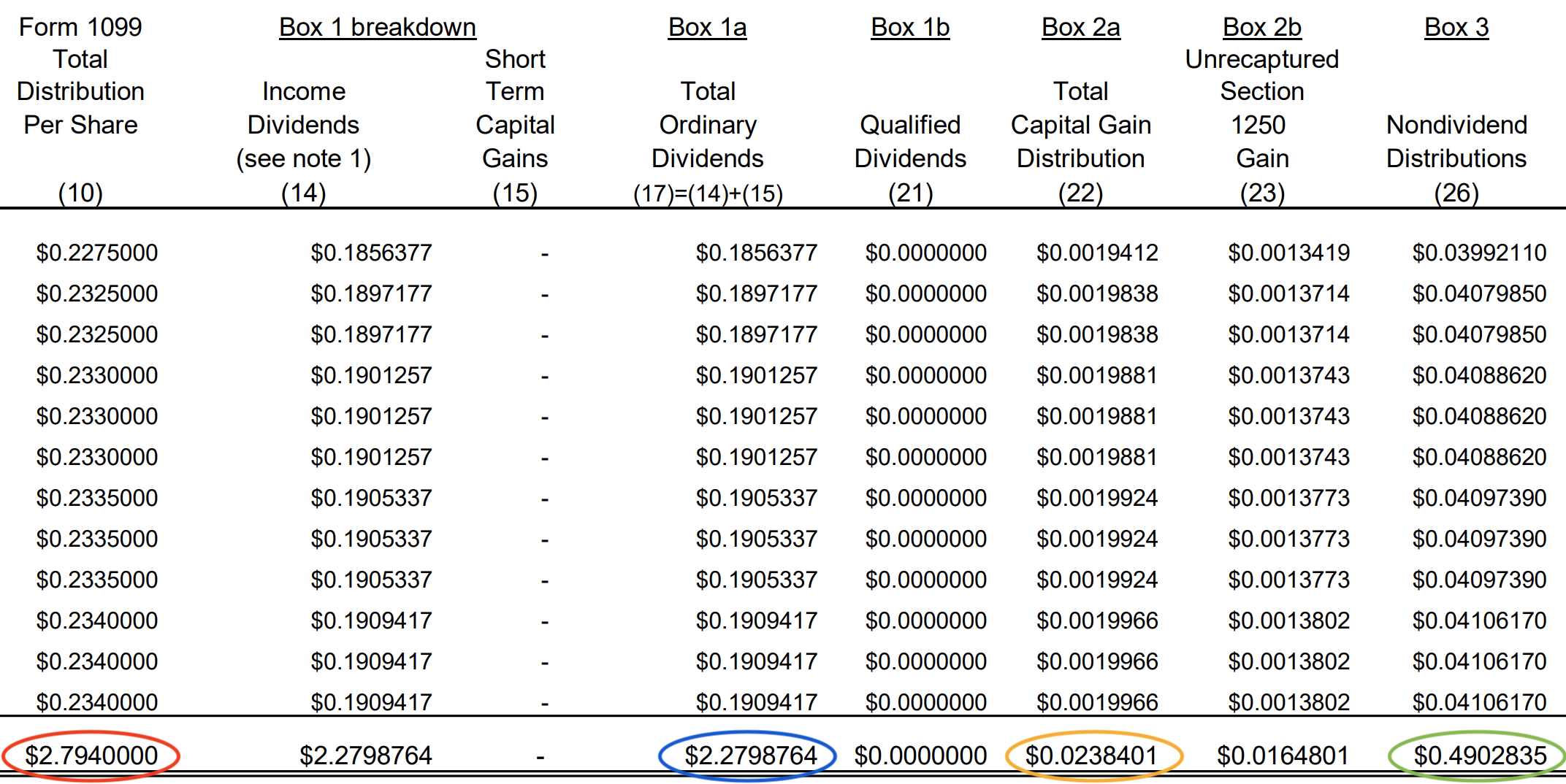

Here is a look at how Realty Income (O) classified the $2.794 of dividends it paid in 2020. The majority of the payout ($2.2798764 circled in blue) was classified as ordinary dividends, with smaller contributions from ROC (circled in green) and capital gains (circled in orange).

If you are a glutton for punishment, you can review some of Realty Income’s (O) 8937 tax forms here.

Looking across hundreds of REITs from 1995 through 2020, data from Nareit shows that ordinary income frequently accounts for around 70% of payouts, with the remainder balanced between long-term capital gains and ROC.

Given this higher mix of ordinary income, which is not subject to the lower long-term capital gains tax rate, investors generally prefer to hold REITs in non-taxable accounts such as IRAs and 401(k)s.

Tax Reform Benefits REITs

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act brought an important benefit for REIT investors: a new 20% deduction on pass-through income through the end of 2025.

This allows individual REIT shareholders to deduct 20% of taxable REIT dividend income they receive, excluding dividends that qualify for the capital gain rates. There is no cap on the deduction, no wage restriction, and investors do not need to itemize deductions to receive this benefit.

The tax law effectively lowered the federal tax rate on ordinary REIT dividends (mortgage REITs included) from 37% to 29.6% for a taxpayer in the highest bracket. This level is still above the 20% maximum tax rate on qualified dividends paid by corporations, but it is a nice step in the right direction.

Given the new pass-through deduction, plus the favorable treatment of REIT dividends classified as a return of capital or a capital gain, owning certain REITs in a taxable account could make sense for some investors, especially those who expect to maintain a marginal tax rate in excess of 30% in retirement.

However, most investors are likely still better off holding REITs in non-taxable accounts such as 401(k)s and Roth IRAs.

This allows individual REIT shareholders to deduct 20% of taxable REIT dividend income they receive, excluding dividends that qualify for the capital gain rates. There is no cap on the deduction, no wage restriction, and investors do not need to itemize deductions to receive this benefit.

The tax law effectively lowered the federal tax rate on ordinary REIT dividends (mortgage REITs included) from 37% to 29.6% for a taxpayer in the highest bracket. This level is still above the 20% maximum tax rate on qualified dividends paid by corporations, but it is a nice step in the right direction.

Given the new pass-through deduction, plus the favorable treatment of REIT dividends classified as a return of capital or a capital gain, owning certain REITs in a taxable account could make sense for some investors, especially those who expect to maintain a marginal tax rate in excess of 30% in retirement.

However, most investors are likely still better off holding REITs in non-taxable accounts such as 401(k)s and Roth IRAs.

Closing Thoughts on REIT Taxes

The non-qualified nature of most REIT dividends means that the majority of their payouts are generally taxed at ordinary income rates rather than the lower long-term capital gains rate that applies to qualified dividends.

As a result, tax-advantaged accounts such as IRAs and 401(k)s are typically better suited to take full advantage of REIT dividends.

As a result, tax-advantaged accounts such as IRAs and 401(k)s are typically better suited to take full advantage of REIT dividends.