Is Ford's (F) Dividend Safe?

Ford’s (F) dividend yield has not been this high since shortly before the company suspended its payout in 2006.

Following the carmaker’s disappointing second-quarter earnings report and rather vague plans for large-scale restructuring in the years ahead, which sent Ford’s stock price to its lowest level since late 2012, some income investors are wondering if the company's current dividend is safe.

Before analyzing Ford’s situation, it’s worth reviewing the company’s past. Several decades of history can teach you a lot about a company’s ability to pay a reliable dividend.

Ford paid out its first dividend way back in 1956, but the company’s track record leaves a lot to be desired. In fact, since 1980, the company has cut its dividend four times.

As you might have guessed, Ford’s historical dividend cuts coincided with downturns in automotive sales, which are highly cyclical.

The chart below depicts the seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of U.S. auto sales (green line) and Ford’s total dividends paid (blue bars) from 1976 through the first half of 2016.

The red circles denote periods when Ford reduced its dividend and are wrapped around the trend observed in U.S. vehicle sales during those times.

With U.S. vehicle sales sitting near their prior historical peaks, Ford’s relatively high dividend yield is partly driven by the market’s anxiety that conditions have peaked; another cyclical downturn could be around the corner.

Three of Ford’s four dividend cuts were approximately 10 years apart from each other.

With the company’s last dividend cut occurring in 2006, investors are wondering if history could repeat itself, especially under Ford’s relatively new management team who might have different capital allocation priorities.

Let’s take a closer look at why the company cut its dividend several times in the past 40 years and whether or not another dividend cut could be on the horizon.

1980 Dividend Cut

Ford’s first dividend reduction during the period I analyzed took place in 1980. According to the Washington Post, U.S. automakers’ production was down more than 30% compared to the prior year.

Lower production volume meant that Ford’s large fixed cost base from its manufacturing plants was spread across fewer vehicles, crimping profitability.

Ford posted a record loss of $164 million in the first quarter of 1980 and was on track to lose more than $1 billion for the full year.

General Motors, the largest company in the industry, was the only auto manufacturer that managed to turn a profit.

All of Ford’s losses were attributable to its North American operations, which more than offset profits from non-auto and foreign subsidiaries.

Ford made its biggest dividend cut in its history (at the time), reducing its payout by 70% in 1980 before completely eliminating the dividend in 1982.

With a loss per share of $12.83, $9.40, and 75 cents in 1980, 1981, and 1982, respectively, Ford had little choice but to cut the dividend, which amounted to approximately 16 cents per share in 1979.

Ford’s initial 70% reduction in the dividend saved the company nearly $340 million per year.

Ford began paying dividends again in 1983, but it wasn’t until 1986 that its quarterly payout exceeded the dividend amount it was doling out in 1979. That is far too long for most income investors to wait.

To conclude, Ford’s 1980 dividend cut was caused by weak industry conditions and unproductive manufacturing facilities, particularly in North America.

While there’s not much Ford can do about the cyclical nature of automotive sales, the company clearly needed to improve the cost-effectiveness of its production facilities.

1991 Dividend Cut

Ford’s next dividend cut took place in early 1991.

After sinking to an annual pace of 9-10 million vehicle sales per year in the early 1980s, U.S. vehicle sales rallied sharply to more than 15 million units per year by the end of the decade.

However, U.S. vehicle sales fell nearly 30% from an annual pace of 16 million in January 1990 to less than 12 million just one year later. The U.S. economy had fallen into a recession, reducing demand for vehicles, and the Persian Gulf War also created challenges.

In response to difficult market conditions, management lowered the company’s quarterly payout by 53%, dropping it from 75 cents per share to 40 cents.

Ford was also involved in a $3 billion cost reduction plan at the time. Reducing the dividend saved more than $650 million per year.

Interestingly enough, Ford had previously stated that it did not want to lower its dividend if profits fell during the next normal cyclical downturn. The company had even resisted pressure to significantly boost its dividend during the boom times of the 1980s.

What was management’s excuse when the dividend was ultimately cut? Here’s what Ford’s chairman Harold Poling said:

“The situation we face today is much more than a normal trough in the business cycle and in automotive earnings. The automotive industry is in the midst of one of the toughest and most challenging periods it has ever confronted.”

Indeed, Ford reported a loss in excess of $600 million during the first quarter of 1991 compared to a profit of more than $500 million during the same period just one year earlier.

General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler lost a combined $3 billion during the first quarter of 1991 – the worst period ever for the automotive industry at the time (cyclical, capital-intensive businesses can be lethal).

Ford wasn’t the only company to cut its dividend during this time. Many companies enjoyed a strong gain in profits (and corporate largesse) during the 1980s and somewhat lackadaisically paid out generous dividends to keep shareholders satisfied.

According to the Commerce Department, American corporations had nearly doubled their payout ratio from 23% in 1980 to 44% in 1990. Debt was used to finance much of the dividend growth during this period marked by strong business conditions.

Of course, nothing lasts forever. Once the U.S. economy entered a recession, many dividends proved to be vulnerable as companies were burdened with interest payments and increasingly squeezed for cash.

It wasn’t until 1997 that Ford’s dividend surpassed its prior peak reached in 1990. Once again, income investors were left hanging.

2002 Dividend Cut

After bottoming out in the early 1990s, Ford’s dividend more than tripled over the next decade.

The company’s next dividend cut was announced in early 2002 when management cut Ford’s quarterly dividend from 10 cents per share to 5 cents, representing a decline of 50%.

The U.S. economy had entered a recession in recent years, but U.S. vehicle sales remained surprisingly resilient – above a 15 million annual rate throughout the entire period.

Prior to announcing its dividend reduction, Ford had more than $16 billion in cash, and analysts didn’t believe the company needed to slash its dividend.

Even Ford’s CFO said he didn’t see any reason to suggest Ford cut its dividend during the summer of 2001.

Why then did Ford cut its dividend?

The company was experiencing intense competition from low-cost foreign competition, incurring heavy marketing costs (dealer incentives were out of control), and facing heavy expenses related to quality issues (e.g. ignition lawsuit; Firestone tire recall; issuing longer product warranties).

Ford was handicapped in many ways that would severely hurt the business heading into the financial crisis as it continued hemorrhaging market share to lower-cost foreign competitors.

For example, according to the Wall Street Journal, Ford’s labor contract with the United Auto Workers union did not allow Ford to close any plants unless the company could prove it was in an economic crisis!

It’s no wonder why Ford’s market share continued to slip and earnings were eroding despite reasonably strong U.S. vehicle sales.

Ford reported a multibillion-dollar pretax loss in its automotive segment in 2001 and lost several hundred million dollars in 2002. The company’s credit rating from Standard & Poor’s was also lowered from A in 2000 to BBB+ in 2001 and BBB- in 2003.

While Ford wasn’t necessarily in a dangerous financial situation or facing another deep trough in vehicle sales, the dividend cut provided the company with some breathing room as it began to more seriously clean up its act.

The dividend reduction saved over $1 billion per year, helping Ford handle its debt load and improve productivity in an effort to stabilize its market position and bring its auto business back to breakeven.

The carmaker kicked off a large number of restructuring actions intended to generate $9 billion in annual cost savings by the mid-2000s – just in time for the company’s next dividend cut.

2006 Dividend Cut

After initialing slicing its dividend in half, Ford announced it was suspending its dividend altogether in late 2006. The company would not begin making dividend payments again until 2012.

At the time of the dividend cut, the auto market had not yet severely corrected (it began to fall in earnest in early 2008).

However, Ford’s auto segment had lost money for six consecutive years, including a loss in excess of $1.5 billion in 2005 (compared to dividends paid of approximately $730 million).

Ford faced headwinds from high gas prices, which resulted in consumers buying fewer SUVs and trucks in favor of smaller cars and crossover vehicles.

The company also added two extra years to the powertrain warranty of its cars and trucks and took other steps to try and improve the resale value of its vehicles. These moves would further erode the firm’s earnings.

By the end of 2006, Ford’s S&P credit rating had fallen well below investment grade to a B with a negative outlook. Ford was in clear need of a major turnaround effort if it wanted to survive for the long term.

The company’s U.S. market share had declined from close to 26% in the early 1990s to less than 19% in 2005. The outlook for Ford was dire.

Cutting the dividend was part of Ford’s massive restructuring plan, which included reducing its North American workforce by nearly 30% and shuttering over 25% of its production capacity.

The New Ford

Ford has clearly experienced a number of rough patches over its lifetime.

While some of its challenges were caused by the cyclical nature of the auto cycle, a lot of its issues were the result of many poor operational and financial decisions made by management.

These strategic oversights compounded over the course of several decades, gradually eroding Ford’s market share and creating an existential threat to the entire company.

Today, Ford is arguably in a structurally healthier and more flexible position that enhances the safety of its dividend payment.

The company ended 2017 with only 61 manufacturing plants, which is down significantly from the 113 plants run by Ford in 2005.

Ford also has about 200,000 employees today compared to 300,000 employees in 2005. Many of its union labor contracts have been modified as well to provide Ford with additional flexibility to manage through the next downturn.

The company also sold or exited all but two of its brands (Ford and Lincoln) and is eliminating all but two of its North American Ford car models to better focus the firm on its strongest opportunities.

From 2015 through 2017, Ford’s automotive segment generated cumulative pre-tax income of $25.5 billion (excluding special items) compared to total dividend payments of $8.3 billion. Its automotive operating margin averaged over 6% during this time, its highest level since at least the 1990s.

Ford has clearly been on a much more encouraging trajectory in recent years and seems better positioned for the industry’s next down cycle. However, the company has bigger issues to worry about over the next decade.

The Auto Industry is Evolving

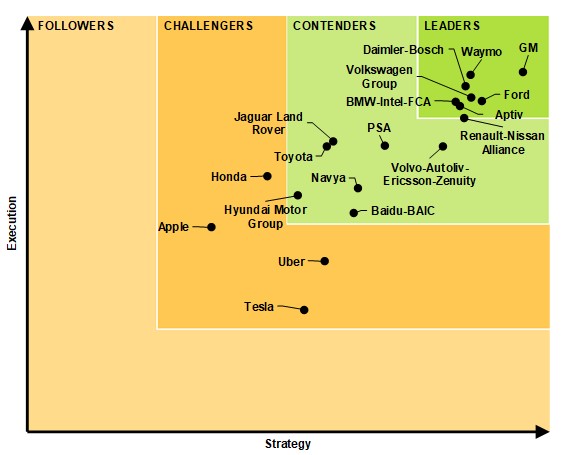

The century-old automotive industry is facing somewhat of an identify crisis. Apple, Tesla, Waymo (Google), and Uber are just several of the key non-traditional rivals vying for a piece of Ford’s market as the battle for self-driving cars, electric vehicles, and ride-sharing services heats up.

In fact, thanks to the rise of car sharing programs, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) believes that by 2030 the stock of cars could fall from 270 to 212 million in the U.S., and 55% of all new vehicles may be electric cars by then.

Perhaps more concerning, PwC also estimates that legacy automakers’ share of global profits could fall from about 85% today to just 50% in 2030 as new entrants from the technology sector push into the evolving transportation market.

Per Navigant Research, the top five companies in developing automated driving systems are (in order): General Motors (GM), Waymo (Google), Daimler-Bosch, Ford, and Volkswagen. However, the field of competitors is very large and still sorting itself out.

Simply put, traditional automakers will likely have to reinvent themselves over the next decade. And as Ford is demonstrating today, change is not cheap or easy.

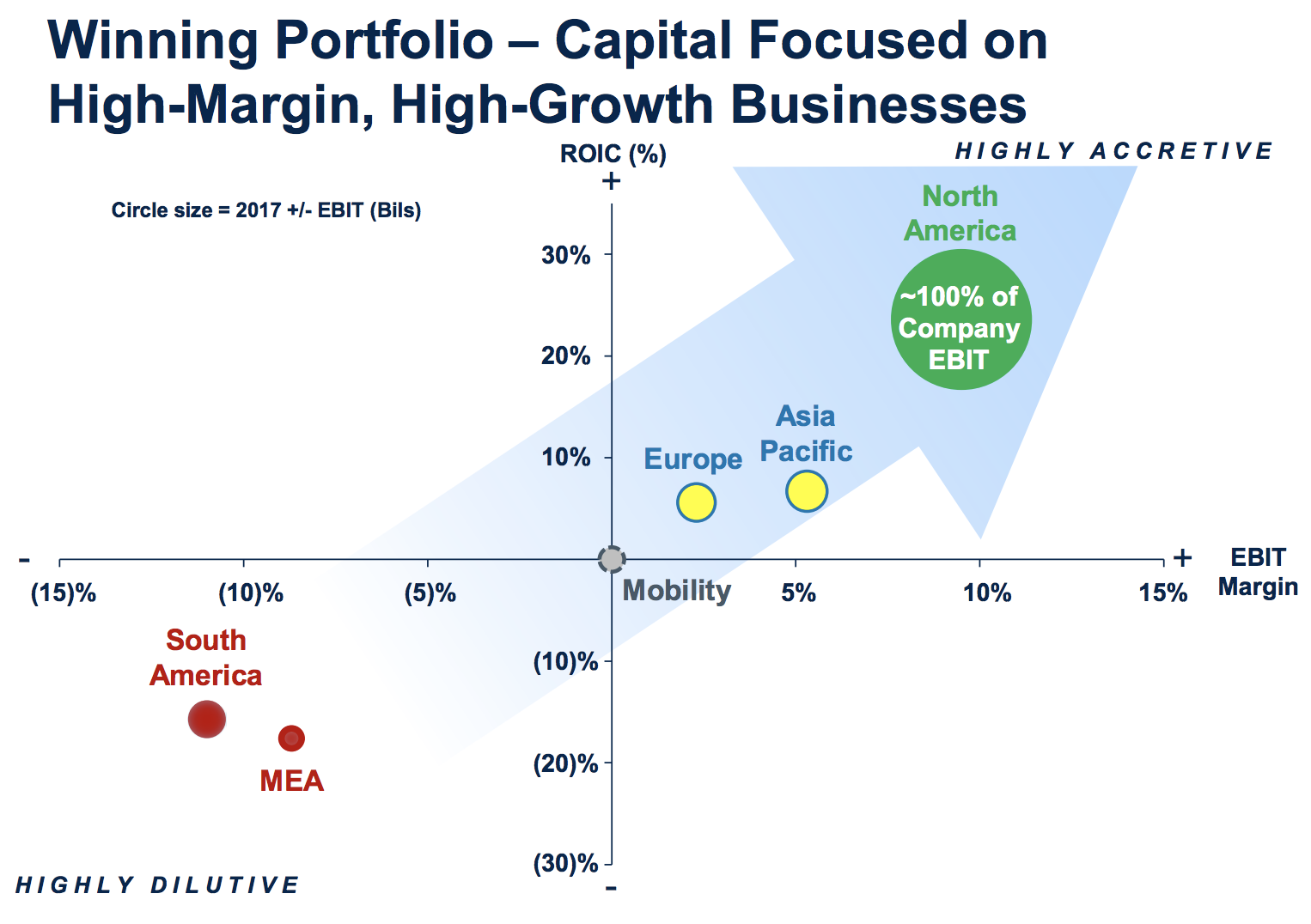

For one thing, Ford’s sprawl outside of North America has proved to be challenging. Currency headwinds, changing regulatory conditions (especially in the U.K.), different consumer tastes, and raw material sourcing are just some of the issues management has to deal with, and the outcome hasn’t been great.

As you can see, the company is collectively losing money in international markets. North America accounts for 100% of Ford’s profits.

Furthermore, as Bloomberg noted, Ford’s sales in China dropped 25% in the first half of 2018. The company’s designs have gone stale in that region, which was expected to be a major growth engine. Escalating trade tensions could lead to further troubles.

Meanwhile, Ford’s management knows the company must invest in autonomous cars and electric vehicles if it is to remain relevant. Juggling each of these priorities has proven to be difficult. The business needs to simplify, improve or prune underperforming assets, and focus on the future.

And that’s exactly what management is attempting to do. Ford announced a major restructuring plan that is expected to result in about $7 billion in cash costs over the next three to five years.

However, the company was light on details. Instead of laying out a clear path forward to improve profitable growth, management told investors to expect frequent updates on future conference calls and meetings. Ford even canceled its Capital Markets Day presentation for investors planned in September to continue working on its restructuring plans.

Here is what CEO Jim Hackett stated on the earnings call:

“Now I'd like nothing better than to give you visibility into the specifics of how we may restructure, but I want you to recognize we're mindful of all of our stakeholders here, the employees, dealers, unions, regulators, government officials and investors. Therefore we only can share information publicly once decisions are made.”

Ford will likely exit more of its low-performing businesses, pump money into improving its vehicle portfolio in China, and continue investing aggressively in autonomous and electric vehicles.

The company expects to have invested $4 billion in its autonomous vehicle business by 2023, and Ford previously outlined plans to spend $11 billion by 2022 on electrified vehicles. The cost of evolution is steep.

Despite more restructuring costs and deeper struggles in Europe and China, management continues to target an 8% operating margin (from 4.3% in the second quarter of 2018) and high teens return on invested capital by 2020.

Investors aren’t so sure. After all, management has done little to inspire confidence in Ford’s traditional business in recent years, and the ultimate returns on investments in self-driving car technologies and electric vehicles are uncertain.

Ford’s Dividend Safety

So what does this all mean for Ford’s dividend?

From a purely financial perspective, Ford’s dividend appears to remain on solid ground today.

Management lowered 2018 adjusted EPS by about 11% to a range of $1.30 to $1.50 per share, which comfortably covers Ford’s current dividend of 60 cents per share.

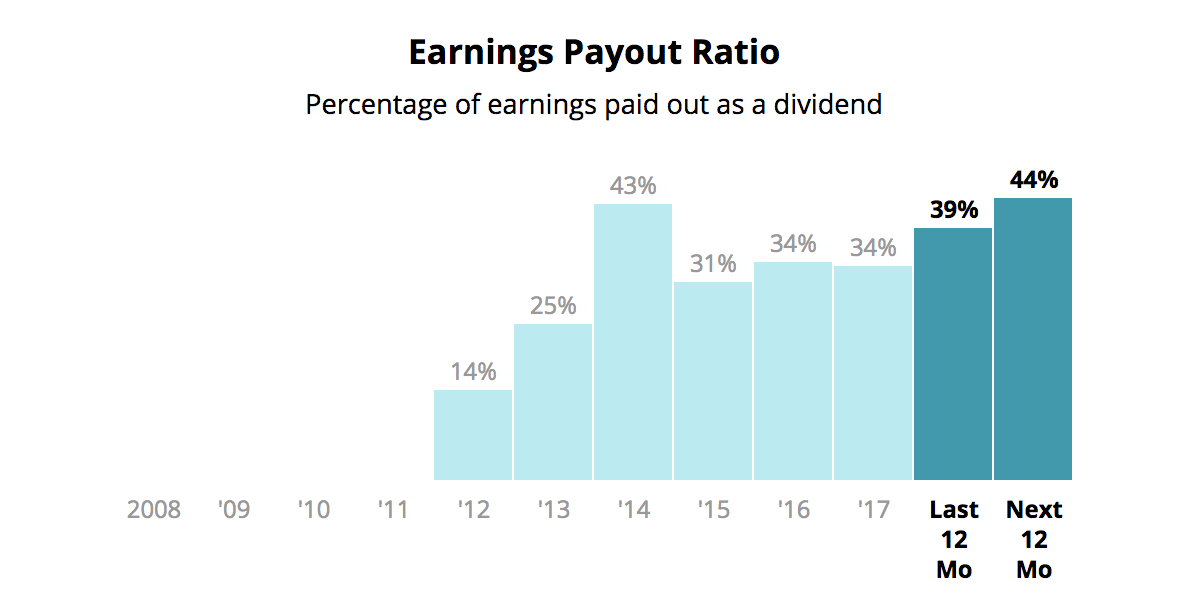

Ford has implemented a hybrid dividend policy, in which it pays out 15 cents per share quarterly, plus a special dividend to achieve a 40% to 50% adjusted EPS payout ratio. The company believes its policy will make the current quarterly dividend sustainable in the long term.

As you can see, Ford’s payout ratio is expected to remain in the targeted range over the next year. However, there is less flexibility for a generous special dividend.

Ford’s regular dividend (excluding the annual special dividend) amounts to about $2.4 billion each year. While that is a lot of cash, the company has a balance sheet that can be used to help protect the regular dividend during the next downturn.

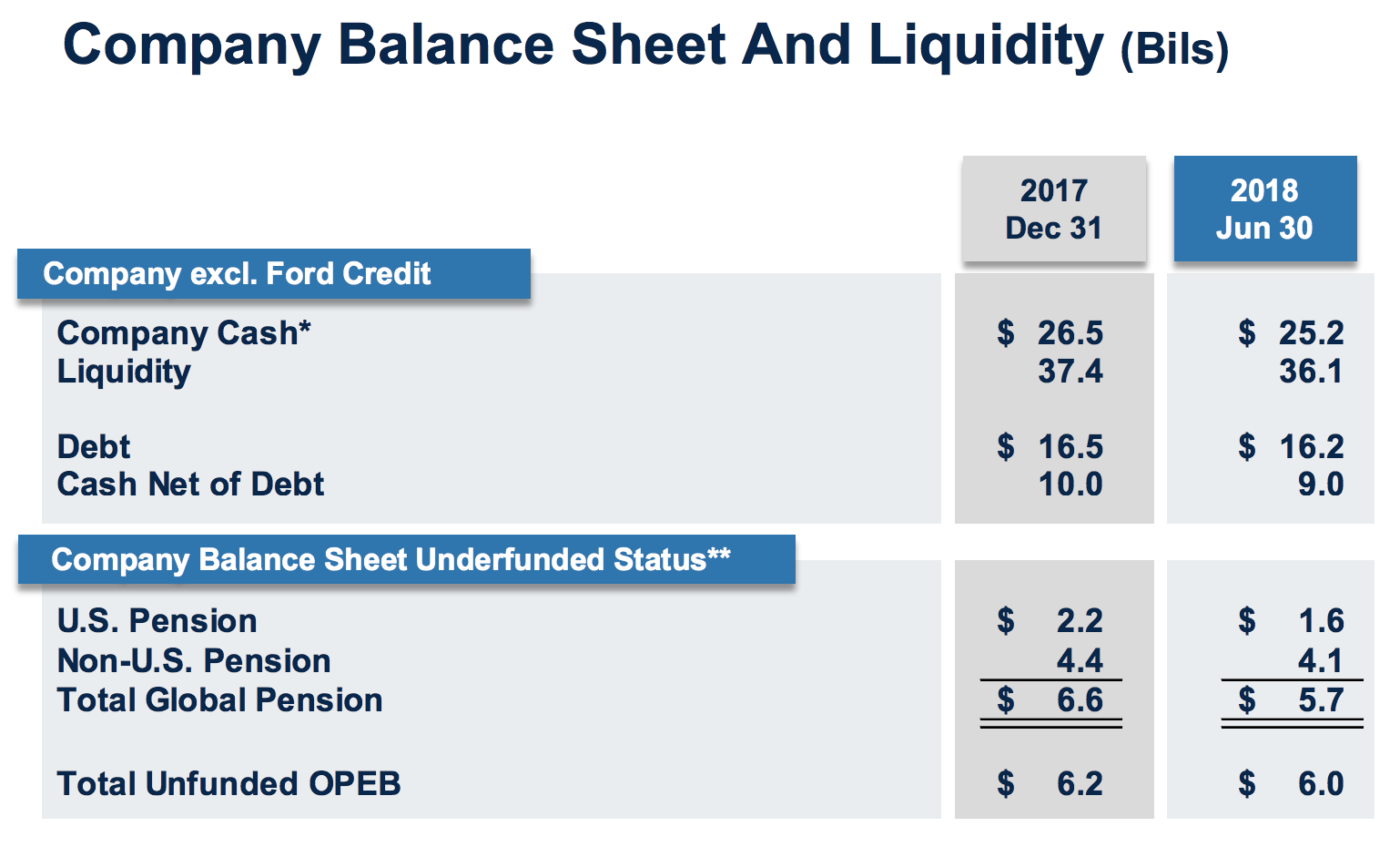

As you can see, Ford (excluding its financing arm) holds just over $25 billion in cash on hand, which is more than its debt ($16.2 billion). Another $10+ billion of liquidity is available through the firm’s credit facility.

Management targets an average ongoing company cash balance of $20 billion, so there is some flexibility behind Ford’s current positioning, even despite recent challenges.

And, as the company stated in its quarterly filing:

“We expect to have periods when we will be above or below this amount due to: (i) future cash flow expectations, such as for investments in future opportunities, capital investments, debt maturities, pension contributions, or restructuring requirements, (ii) short-term timing differences, and (iii) changes in the global economic environment.”

Ford’s payout ratio looks reasonable and its balance sheet is in decent shape. While we have seen that the firm needs to invest heavily to redesign its business model, Ford believes its ongoing capital spending needs will actually moderate from $7.5 billion in 2017 to about $7 billion annually starting in 2020. That provides more room for investments and the regular dividend.

Of course, the big wild card over the short term is still where the automotive cycle goes. There are plenty of questions surrounding Ford’s performance during the next downturn.

Will the company’s smaller manufacturing footprint and reduced labor force allow its auto segment to at least break even?

Will Ford’s financial services arm, which is levered 10:1 with over $100 billion in debt and the lowest investment grade credit rating from S&P, face unprecedented challenges if some of its loans go bad (especially subprime)?

Ford’s operational improvements, reasonably healthy balance sheet, $10+ billion in available credit lines, and improved cash management philosophy seems like enough for the company to finally maintain its dividend during the next industry downturn.

That last point is important. Ford’s current dividend policy was built to survive through a downturn. While management thought the same thing back in the early 1990s and was proven wrong, this time seems different.

The new and improved Ford is much more competitive and streamlined. The company’s regular quarterly dividend amounts to roughly $2.4 billion per year, which is less than the annual dividends it paid in 2000 despite the company’s much improved profitability today.

Ford’s previous management team also conducted a stress test that modeled a hypothetical future U.S. industry downturn in which sales declined by as much as 36% from 2015.

Thanks to the company’s improved North American cost structure and Ford’s strong liquidity, the regular dividend was expected to remain safe in such an event.

However, the management team has since changed. CEO Hackett took over in 2017 and is much more focused on investing in driverless cars, electric vehicles, and vehicle management as a service.

In other words, Ford now has greater investment needs, so it’s possible the company’s dividend will not be immune to a cut in a future industry downturn.

Ford’s major new restructuring initiative has some dividend investors worried that the company might put its payout on the chopping block even sooner, but that does not seem very likely.

For example, while details were lacking, during the last earnings call Ford’s management made the following comments about the new restructuring plan:

“It's important to highlight that we believe we can fund these cash effects without impinging on our other capital outlays including investments for growth and our regular dividend.”

The company issued a similar statement in its quarterly filing:

“Based on our planning assumptions, we believe we have sufficient liquidity and capital resources to continue to invest in new products and services, pay our debts and obligations as and when they come due, pay a sustainable regular dividend at the current level, and provide protection within an uncertain global economic environment.”

Investors banking on Ford’s generous regular dividend don’t have much to worry about over the short term.

However, the special dividend seems likely to be reduced or perhaps even skipped next year given Ford’s rising payout ratio, performance issues abroad, substantial cash restructuring costs, and need for more investment in the industry’s future growth drivers.

And whenever the next industry downturn occurs, it is less clear how Ford’s current management team will prioritize growth investments and the dividend. Perhaps management will have more details to share as the restructuring plan begins to firm up.

Closing Thoughts on Ford’s Dividend Safety

Dividend investors have experienced somewhat of a joyride with Ford over the last 40 years. The company has slashed its payout four times and even stopped paying dividends altogether twice. The auto industry is extremely competitive, cyclical, and capital intensive.

However, barring an unprecedented shock in auto loans’ credit quality or a nasty combination of events (e.g. spiking gasoline prices, intensified marketing incentives / pricing pressure, total collapse in industry volumes), Ford’s regular quarterly dividend seems likely to remain safe, at least over the short term.

Continuation of the company’s special dividend is much more suspect over the coming years for a number of reasons (rising payout ratio, high cash restructuring costs, need for greater investment in elective and self-driving vehicles).

Ford is largely a “show me” story as management seeks to restore credibility with investors (optimizing Ford’s product portfolio and geographic footprint is no small task), prove itself during the next dip in U.S. vehicle sales, and adapt the company’s business model to a future world that could require far fewer cars.

While income investors will continue to be attracted to Ford’s high dividend yield, this is still volatile stock that will get whacked during the next downturn – even if the dividend remains safe. The company faces a relatively wide range of potential outcomes over the next decade.

Ford’s stock often looks “cheap” due to these concerns, but an investment in the carmaker is not for the faint of heart. Conservative investors, especially those focused on capital preservation, are likely better served avoiding this stock, or at least keeping it as a relatively small position as part of a well-diversified portfolio.