Simon's Dividend Risk Rises as More Tenants Become Distressed

The risk to Simon's dividend hinges largely on how long store closures persist and how optimistic management is about retail performance once stores reopen. A further downgrade to Unsafe could be issued quickly if closures appear they will last longer or if widespread rent defaults become likely.

The outlook for extended store closures and rent collections has materially weakened since then. We expect this to pressure Simon's ability to cover its dividend, protect its balance sheet, and invest in its necessary redevelopment projects.

As a result, we are downgrading Simon's Dividend Safety Score from Borderline Safe to Unsafe and believe it would be prudent for management to reduce the dividend substantially, perhaps as soon as its next earnings report in early May.

Since mid-March, it's become increasingly clear that rent collection will be a major ongoing issue for retail REITs.

Nareit, a producer of REIT research, recently conducted a survey of 54 publicly-listed REITs and found data suggesting that malls have collected less than 25% of their rent this month as of mid-April.

Simon's mall portfolio has historically been praised for its superior locations, but that doesn't matter when everything is closed and its tenants become more strained by the day.

In just the past week, several of Simon's largest tenants have issued dire warnings.

Simon's biggest tenant, Gap (3.4% of rent), warned on Thursday that it could run out of money in the next 12 months. It has suspended rent payments and will look to terminate some leases.

The mall REIT's next largest tenant, L Brands (2.2% of rent), recently saw a buyer for its Victoria's Secret chain back out of the deal due to the coronavirus, creating further uncertainty about its ability to survive.

Other top 10 tenants Tapestry (1.5% of rent) and Capri (1.2%) saw their credit ratings downgraded to junk by Fitch.

Mall anchors (around 30% of Simon's square footage) are hurting just as much, if not more.

Macy's (0.3% of rent, 12% of square footage) said it is looking to raise up to $5 billion to avoid bankruptcy.

J.C. Penney (0.3% of rent, 5.6% of square footage) is already in talks for bankruptcy funding, and Neiman Marcus (0.8% of square footage) is expected to file for bankruptcy as soon as this Sunday.

Besides rent payment issues, 7.6% of Simon's leases expire in 2020, and another 2% are month-to-month. The REIT's 95% occupancy rate seems likely to fall since finding replacement tenants will be extremely difficult in this environment.

If more of Simon's storefronts become vacant, shoppers have less incentive to visit its malls. And that could create a downward spiral if it reduces the perceived value of Simon's properties in the eyes of prospective tenants.

Even once malls are allowed to reopen, perhaps by this summer, we believe crowds will be slow to return.

Lingering contagion concerns could persist, and shelter-at-home orders have likely sped up the trend towards online shopping, which accounted for only 11% of total U.S. retail sales in 2019.

The bottom line is that the coronavirus has a good chance of accelerating the retail revolution, which could still be in the early innings.

As a result, we are doubtful that Simon will ever be able to collect full rent from many of its distressed tenants, and a return to its past occupancy rates could be a struggle.

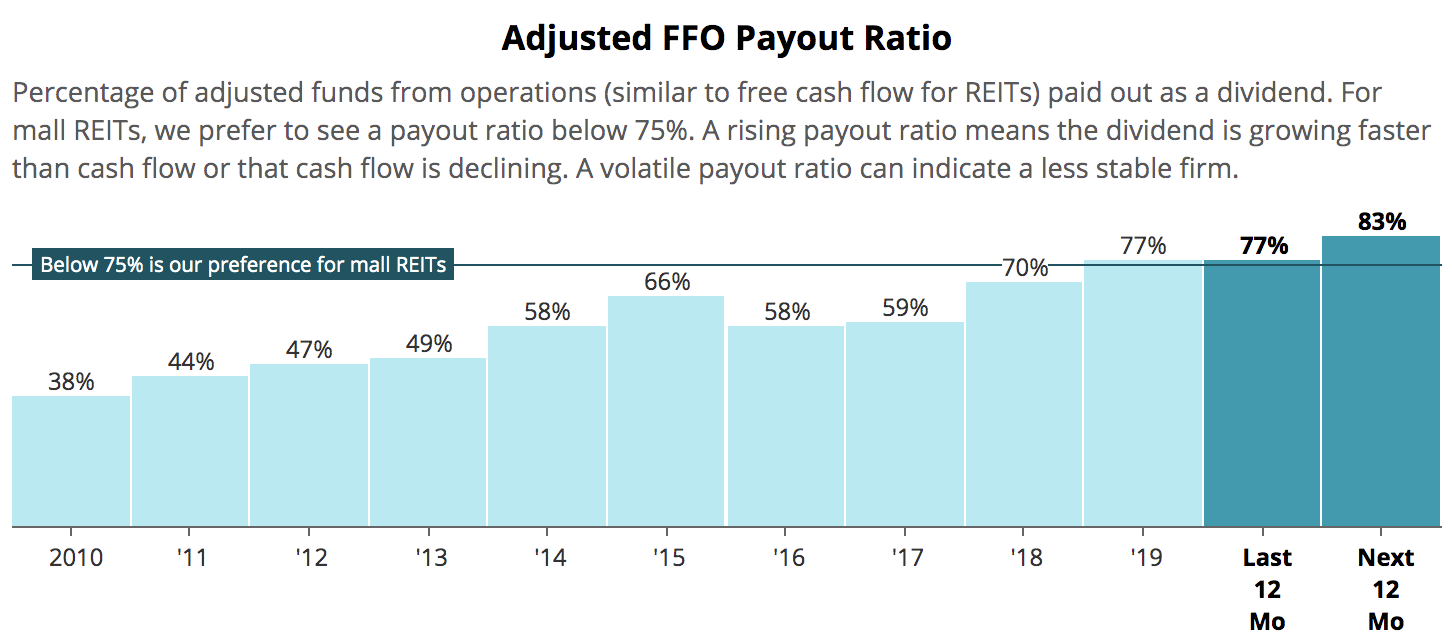

Heading into the pandemic, Simon had a moderate payout ratio of 77%. In theory, the firm's cash flow could take about a 20% hit and still cover the dividend.

Analysts have begun reducing their cash flow estimates, but we believe they have much further to fall. We would not be surprised if Simon's payout ratio exceeds 100% once the dust settles.

While Simon has an A credit rating from Standard & Poor's and $7 billion of available borrowing capacity under its credit revolver and term loan facilities, it seems unlikely that the REIT would be comfortable increasing leverage to cover the dividend in this environment.

After all, if brick-and-mortar retail headwinds are now accelerating due to the pandemic, Simon faces even greater urgency to execute on its redevelopment activities, which are underway at more than 30 of its 200-plus properties.

Space previously leased to department stores is being swapped out for restaurants, gyms, hotels, offices, apartments, and entertainment centers.

In mid-2019 management said the company's redevelopment plans were only about a third finished, suggesting it could take several more years to get the entire portfolio better aligned with today's real estate trends.

Rather than being able to run its existing properties for cash (under $200 million in maintenance capital expenditures each year), Simon had earmarked $1.4 billion in total costs this year for its current slate of redevelopment projects, with more spending expected in future years.

After paying its $2.6 billion dividend, Simon previously generated between $1.3 billion and $1.4 billion of cash which could cover its redevelopment projects.

But with retained cash flow evaporating due to COVID-19 and a sharp rebound looking extremely unlikely, Simon faces a tough choice.

To make ends meet, Simon must either raise more funds (issue equity or debt) until cash flow hopefully improves, slow its reinvestment projects, or cut its dividend.

Reducing the dividend, perhaps by 50% or more, is the easiest lever to pull to preserve more capital, and Simon has done it before. Even in 2009, when Simon's leverage and payout ratio were lower, the firm cut its dividend.

Looking ahead, Simon's stock price obviously reflects a lot of bad news.

After accounting for Simon's planned acquisition of Taubman, we estimate that Simon's 2019 pro forma net operating income (NOI) implies about a 15% capitalization rate based on the REIT's current equity and debt value.

The implied capitalization rate is calculated by dividing a REIT's NOI by its equity and debt. It's far from a perfect measure of value in part because each property is unique, but it provides a helpful framework in this situation.

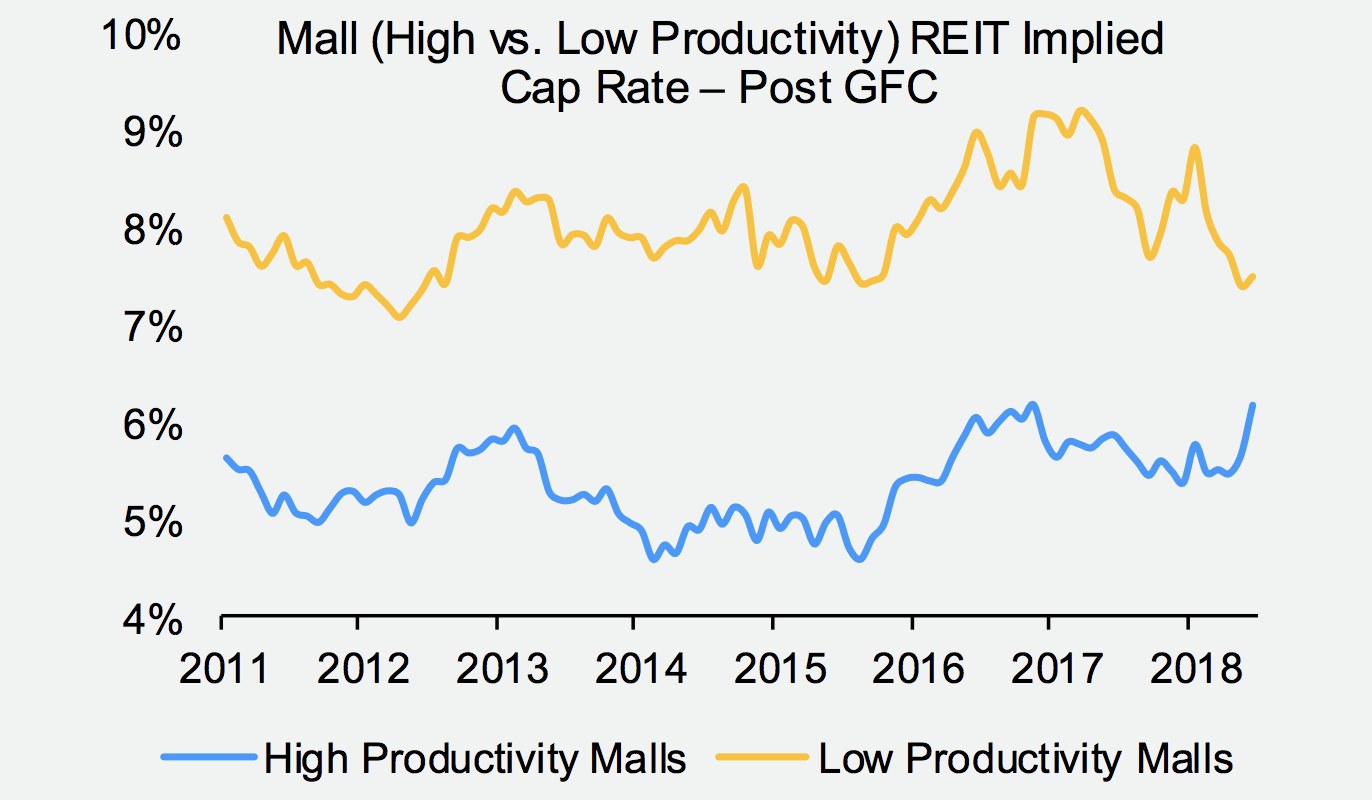

From 2011 through May 2019, mall REITs traded at an implied cap rate around 6% to 8%, depending on the quality of their properties. Higher cap rates represent lower valuations.

Given the recent spike in cap rates, investors are valuing mall REITs much less favorably going forward and likely baking in a material decline in Simon's future NOI.

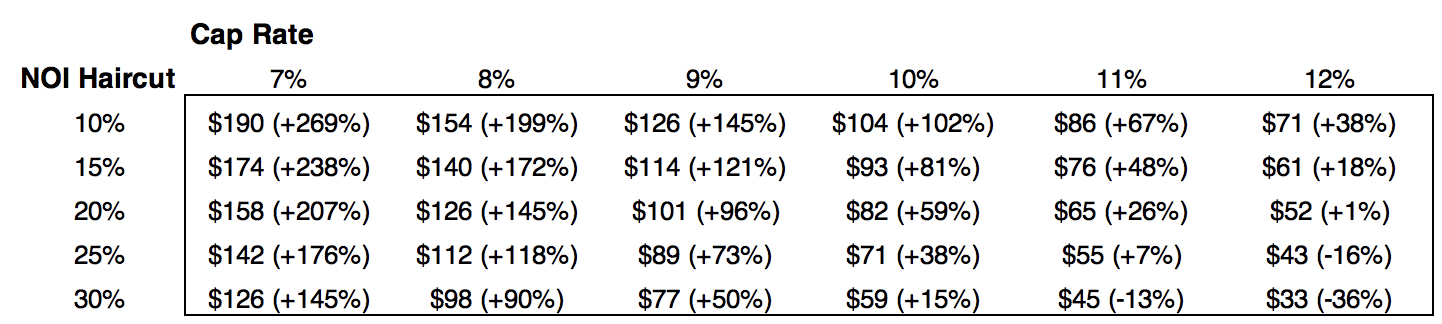

The table below shows how Simon's stock price could change based on different theoretical reductions to its 2019 NOI and the cap rate used.

For example, if Simon's NOI fell only 10% from its 2019 level and investors began to believe Simon's malls were much more durable than they expected and thus deserved to return to a 7% cap rate, then SPG's stock price would, in theory, nearly quadruple from around $51 per share today to $190.

But if Simon's NOI declines by 30% and fails to recover, warranting a 12% cap rate, then SPG's stock price could actually fall by more than 30% from here.

This is a crude and overly simplistic analysis, but the point is that Simon's stock faces a wide range of outcomes to consider, and there is still downside risk.

We remain pessimistic about the long-term future of malls and Simon's ability to return its business to profitable growth anytime soon.

As we discussed several months ago, malls haven't been around that long in the grand scheme of things. The problems malls initially addressed are increasingly being solved elsewhere.

The technology-driven shift in retail distribution and socialization preferences reduces malls' value proposition, threatening to leave a glut of capacity behind.

America's first enclosed mall was built in 1956, and the nation hasn't looked back. About 1,500 malls were built in the U.S. from 1956 through 2005, providing hubs for social gathering and shopping throughout America's booming suburbs.

By 1975, malls accounted for 50% of U.S. retail dollars spent, representing an impressive 13% of GDP. So much property was developed that by 2017 America had an estimated 26 square feet of retail for every person in the country, compared with less than 3 square feet per capita in Europe, according to Time.

But now, in the age of Amazon, many areas of brick-and-mortar retail, including malls, are being forced to right-size their footprints.

Simon has the balance sheet to survive for the foreseeable future, but it's hard to imagine its current dividend making it through as well.

Ultimately, Simon reminds us of Warren Buffett's "cigar butt" investment style, which he explained in Berkshire Hathaway's 1989 annual shareholder letter:

"If you buy a stock at a sufficiently low price, there will usually be some hiccup in the fortunes of the business that gives you a chance to unload at a decent profit, even though the long-term performance of the business may be terrible. I call this the "cigar butt" approach to investing. A cigar butt found on the street that has only one puff left in it may not offer much of a smoke, but the "bargain purchase" will make that puff all profit."

While some current shareholders may be comfortable with that type of approach, Buffett went on to explain why he no longer believes that strategy is ideal:

"Unless you are a liquidator, that kind of approach to buying businesses is foolish. First, the original "bargain" price probably will not turn out to be such a steal after all. In a difficult business, no sooner is one problem solved than another surfaces - never is there just one cockroach in the kitchen.

Second, any initial advantage you secure will be quickly eroded by the low return that the business earns. For example, if you buy a business for $8 million that can be sold or liquidated for $10 million and promptly take either course, you can realize a high return.

But the investment will disappoint if the business is sold for $10 million in ten years and in the interim has annually earned and distributed only a few percent on cost. Time is the friend of the wonderful business, the enemy of the mediocre."

Your guess is as good as ours regarding Simon's short-term performance, especially as REIT investor sentiment remains unusually volatile due to the pandemic.

As conservative investors with fairly concentrated portfolios (20-30 holdings), we prefer to invest in businesses with safer payouts and clearer paths to growing in value in the years ahead. The fast-changing nature of the retail sector has never helped with those objectives.